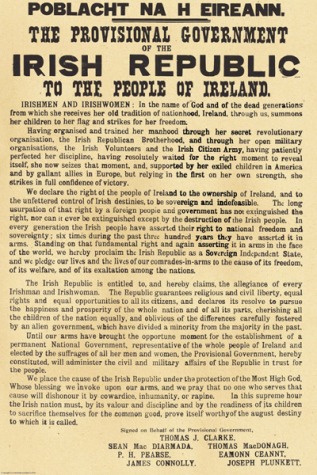

Clare Hollingworth, war reporting and witnessing history

By Ciarán McCabe

Being an eye-witness to historic events is a rare thing for most people. But war correspondents frequently find themselves eye-witnesses to events of international significance, to the ‘first draft of history’. This is owing to the nature of the job. War correspondents – ever since William Howard Russell in the 1850s – have tended to travel from one sphere of conflict to another and have been, inevitably, well placed to witness battles, retreats, genocide and famines.

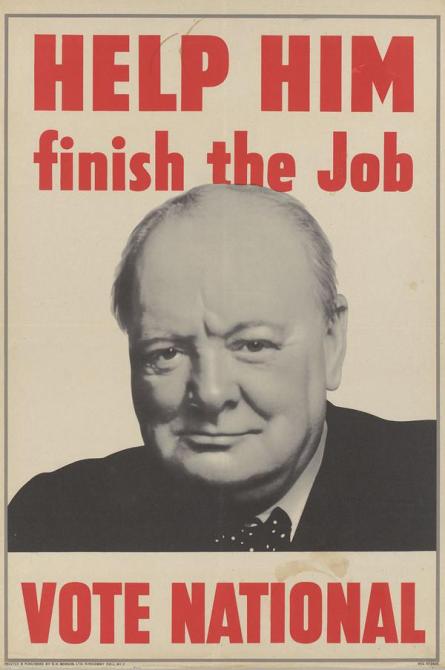

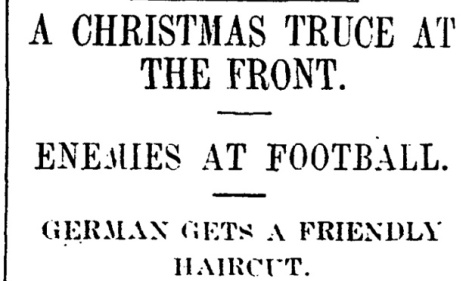

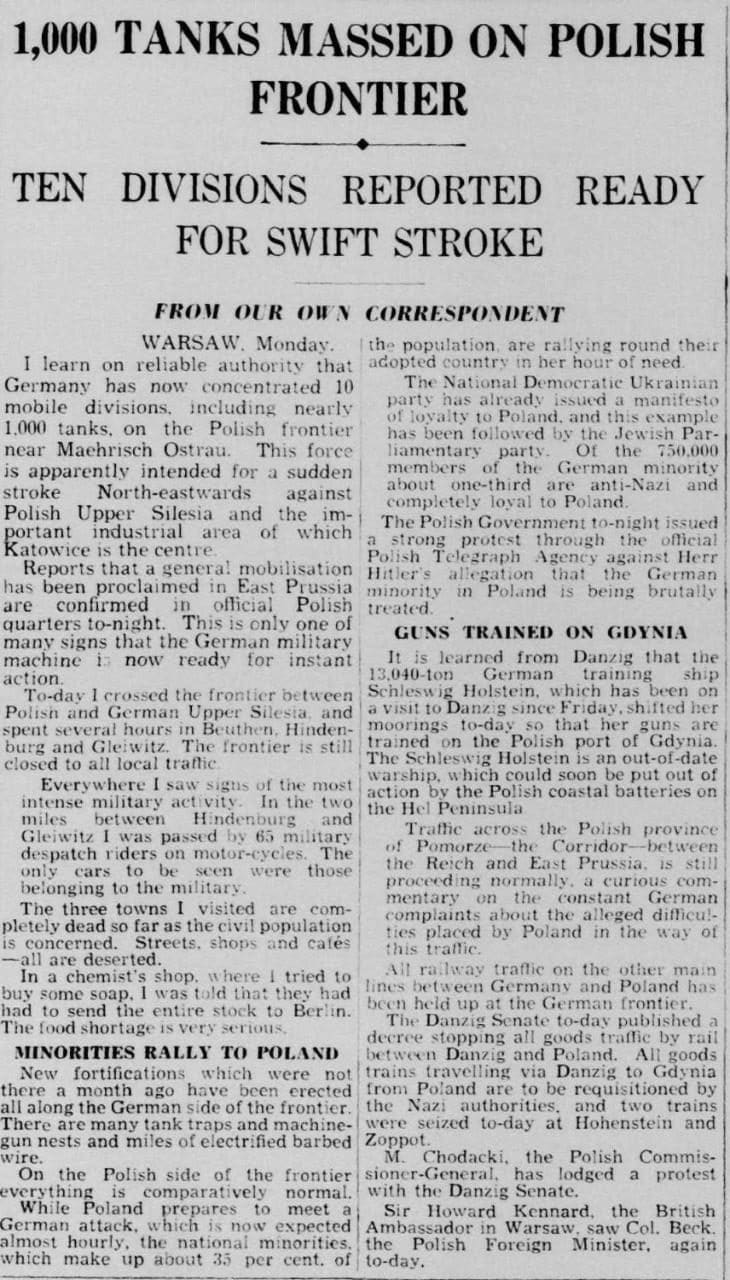

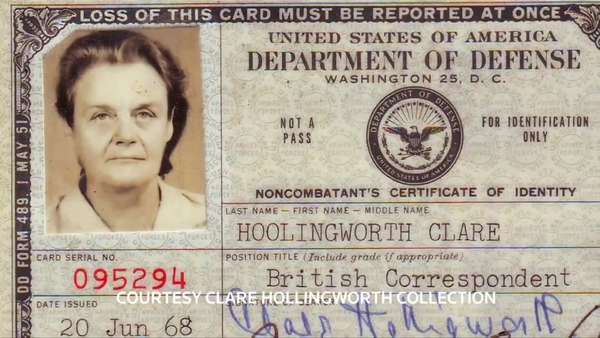

Among the most prolific, well-travelled and influential correspondents of the past century was Clare Hollingworth, who died in January 2017 aged 105 years. Her career was one of numerous exclusives of international significance, including perhaps the ‘scoop of the century’ when she reported on German mobilisation towards the Polish border in late-August 1939. Posted in Katowice as the Daily Telegraph’s war correspondent, Hollingworth borrowed a diplomatic vehicle to cross over into Germany to buy essentials, such as aspirin and wine, in the knowledge that a war was imminent. Driving back through the border, a hessian partition which had been erected along the roadside was blown open by a gust of wind, revealing (in the journalist’s own words) “scores, if not hundreds of tanks” in the valley below. Four days into her first posting as a war correspondent, Hollingworth had just landed the ‘scoop of the century’: the outbreak of World War II. Her published article of 29 August 1939 was headed: ‘1,000 tanks massed on Polish frontier. Ten Divisions reported ready for swift stroke’. (Thirty years later, she secured another world exclusive, in reporting for the Daily Telegraph on the commencement of secret negotiations to end the Vietnam War, an initiative latter scuppered through the cloak-and-dagger intervention of Richard Nixon).

(Image: Clare Hollingworth’s ‘scoop of the century’ (Daily Telegraph, 29 Aug. 1939))

Later in the war, Hollingworth reported from the North African front, regularly from behind enemy lines. Throughout her career her reporting was bolstered by her skill at developing contacts and networks of confidantes: she was well connected to the left-wing Front de Libération Nationale in Algeria, and in 1941 secured the first interview with the Shah of Iran, who, after his fall in 1979, would only speak to her. Hollingworth’s contacts also aided her in identifying and ‘outing’ the Soviet spy, ‘Kim’ Philby, a prominent war and foreign correspondent who defected to the USSR. (Incidentally, Hollingworth’s death came just four weeks after that of Philip Knightley, who was a member of the Sunday Times ‘Insight’ team that investigated Philby’s defection and who also wrote The First Casualty, the multi-edition survey work of the history of war reporting from the Crimean War to the recent Iraq War).

Among the wars Hollingworth reported on first-hand were World War II (1939-45), the French-Algerian War (1954-62), the India-Pakistan War (1965) and Vietnam (1960s), as well as from Maoist China. When the King David Hotel in British Mandate Jerusalem was attacked in 1946 by Irgun, the Zionist terrorist organisation, killing just less than 100 people, mostly British Mandate officials, Hollingworth was on the scene within minutes, having shortly beforehand parked her car around the corner; in 1989 she witnessed the Tiananmen Square massacre from a hotel balcony.

Among the interesting aspects of Hollingworth’s career is her sex. The fact is that the archetypal war reporter is a man – a fact demonstrated in war reporter John Burrowes’s dedication to his 1984 memoirs: ‘To reporters everywhere – and the women who have to suffer them’. Yet, despite the predominance of men among this profession notable women are to be found among the ranks of war correspondents, notable not for their relative novelty (for being women in a heavily gendered profession) but for their innovative reporting of conflict: Irish native Kathleen ‘Kit’ Blake Coleman, Virginia Cowles, Martha Gellhorn, and, right through to Marie Colvin, who was killed in Syria in 2012. In his illuminating The War Correspondent (2nd ed., 2016), Greg McLaughlin considers various commentators’ views on the significance of rising numbers of women correspondents in recent decades: some see this phenomenon as encouraging ‘a less gung-ho, more human-oriented sensibility’ to reporting, while for others, women reporters are more likely to cover unfashionable stories (the example of the East Timor crisis in 1999 is cited by McLaughlin), in contrast to their male counterparts, who are more likely to be career-driven and to throw themselves into headline-grabbing conflict reporting.

In noting the role of women as correspondents in conflict zones, it is interesting that just last month, the magazine Military Review (an official publication of the US armed forces) published a poignant photograph taken by US Army camerawoman Specialist Hilda Clayton, of the moment she was killed by an accidental mortar explosion during a training exercise in Laghman province, Afghanistan on 2 July 2013. In explaining the publication of the photograph, the magazine was eager to assert that women photographers (in this case, soldier correspondents) were as much a part of the conflict zone as their male colleagues: ‘Not only did Clayton help document activities aimed at shaping and strengthening the partnership but she also shared in the risk by participating in the effort … Clayton’s death symbolizes how female soldiers are increasingly exposed to hazardous situations in training and in combat on par with their male counterparts.’

Useful articles and obituaries can be found online at:

http://time.com/4520940/clare-hollingworth-war-correspondent-birthday-hong-kong/

Greg McLaughlin, The War Correspondent (2nd ed., London, 2016).

The ‘Time in the Slime’: not quite counting down to the millennium

Millennium Clock Source: Pinterest

The Millennium Clock was design to be a significant part of the millennium celebrations in Dublin city. The six-ton, £250,000 clock was sponsored by the Irish National Lottery. The clock was placed underwater at O’Connell Street Bridge in March 1996 and its primary function was to countdown to the year 2000. It consisted of a 1.9 meter deep, 7.8 meter-wide steel frame with luminous green rods that displayed the time. It also included a kiosk, located on O’Connell Bridge which recorded the time remaining on the clock on a postcard, thus providing a unique memento.

However, difficulties with the clock and its position in the river were experienced from the onset. Firstly, as anyone who is familiar with the pristine waters of the River Liffey can testify, the placing of a clock underneath its surface was a recipe for disappointment. Hence the granting of its colloquial title by the citizenry of Dublin: ‘the time in the slime.’ Three days after the clock was switched on it was to disappear. Despite reports in a national newspaper that this may have been the work of the magician Paul Daniels, it was in fact removed to facilitate a boat race. Indeed, it was reckoned that this would be a regular feature of the clock’s future.

The clock was to experience a number of mechanical faults over its short life, including displaying the wrong time. In addition to these mechanical difficulties, there were mounting costs associated with keeping the clock clean. It was removed from the river permanently by the end of the year. The Irish difficulty with electronic devices should have perhaps served as a warning to Irish politicians when they embarked on the electronic voting fiasco a few years later. This was to involve spending €54 million on 7,500 electronic voting machines that were widely unpopular among the public and never used! Perhaps the last word on the clock should go to the National Lottery spokesperson: ‘When it’s up and running, we are confident that people will say it was worth it.’ We will leave it up to you to decide if that was the case.

Further reading

‘The Millennium Clock’ in Irish Independent, 2 April 2016, available at (http://www.independent.ie/unsorted/features/the-millennium-clock-26410316.html) (22 May 2017)

‘Liffey clock to be tock of the town in March’ in Irish Times, 26 Jan. 1996, available at (http://www.irishtimes.com/news/liffey-clock-to-be-tock-of-the-town-in-march-1.25327) (22 May 2017).Evening Herald, Wednesday, 1 May 1996

‘Time in the Slime is the Clock in Dry Dock’ in Irish Times, 20 Mar. 1996, available at (http://www.irishtimes.com/news/time-in-the-slime-is-the-clock-in-dry-dock-1.35492) (22 May 2017).

Evening Herald, Wednesday, 1 May 1996

Bio:

Adrian Kirwan, co-editor of Holinshed Revisited completed a Ph.D. at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, in 2017. His research focuses on the interaction between science, technology, and society. He is currently researching the history of early research into radioactivity in Ireland. More about his research can be found here.

Irish war correspondents in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries

In 1927 the Irish war correspondent Francis McCullagh (1874-1956) was described as follows:

‘Trotsky of Russia knows Francis McCullagh. So does President Calles of Mexico. Peter, the king of Serbia, was McCullagh’s friend. The headhunters of the upper Amazon list Francis McCullagh as one of their principal deities. The warring tribes of Morocco call him blood brother. A room is always ready for him in the imperial palace of Siam. The latchstrings of hundreds of Siberian peasant huts are out in anticipation of his coming.’

The writer of the above description, quoted in John Horgan’s 2009 article on McCullagh, certainly deployed verbal embroidery in recording the international influence of the Irish correspondent. Hyperbole aside, the description captures the reality that McCullagh, the son of an Omagh publican and who wrote for (among many titles) the New York Herald, the Daily News, the Irish Independent and the Japan Times, was by the early-twentieth century, a war correspondent of significant standing throughout the world. Fluent in (or certainly in possession of a good grasp of) numerous languages, McCullagh negotiated his way into the front-line of battle and into the presence of world leaders. In 1905 his reporting of Japan’s sinking of the Russian fleet was a world exclusive. In the following six years McCullagh reported on the Young Turks’ revolt in Turkey, the revolution in Portugal and the Italian invasion of Libya. He returned to Russia in 1918, in the months following the Bolshevik Revolution and participated in the White Russian inquiry into the execution of the Romanovs. Later assignments included the Mexican revolt of the 1920s and the Spanish Civil War the following decade. As Horgan notes McCullagh’s reporting has its shortcomings, most notably its unashamedly partisan stances in its witness accounts of significant world events. The instance of McCullagh points to the prominence of Irish war correspondents from the mid-nineteenth century.

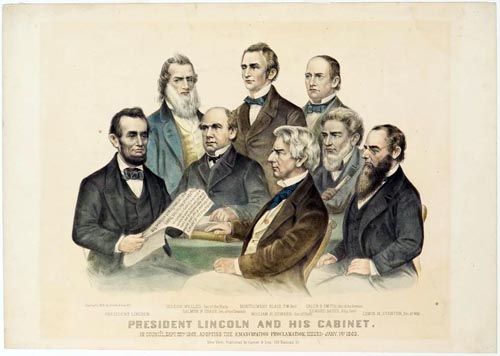

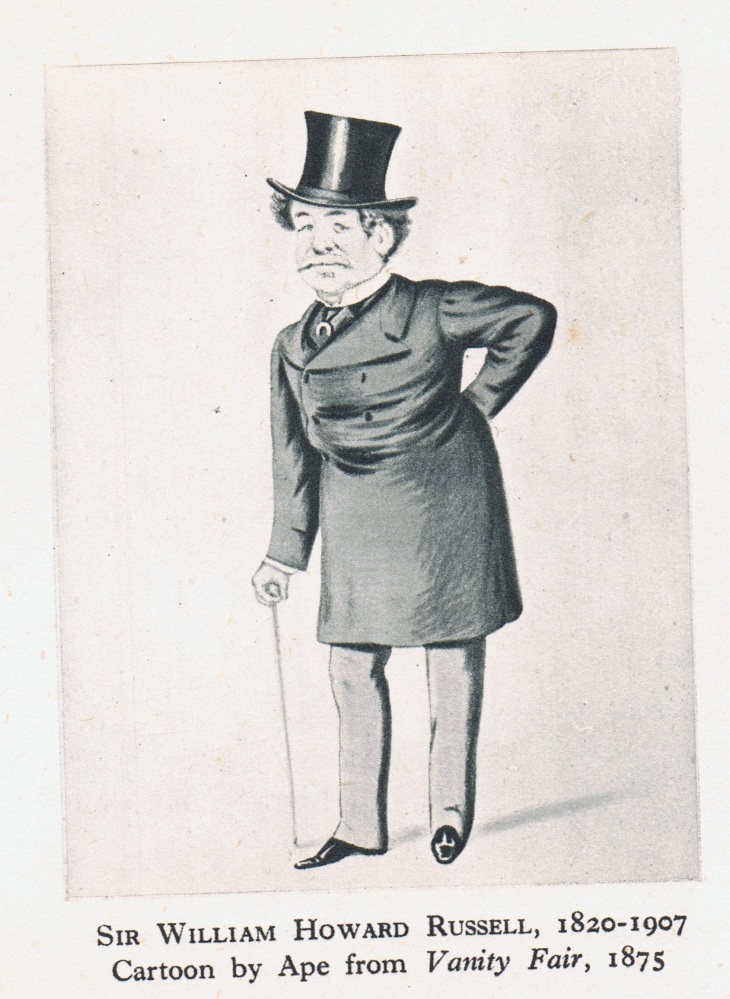

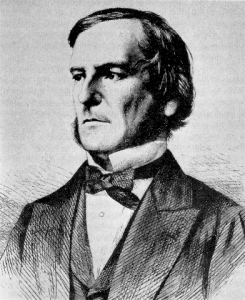

Philip Knightley rightly commences his First Casualty, still the best general history of war reporting, with the Dubliner, William Howard Russell, whose reporting of the Crimean War of the mid-1850s is seen as laying the foundations of modern war reporting. Russell, whose reporting of woeful military tactics and insufficient supply and medical services in the British army, contributed to the fall of the government in 1855 under the pressure of disillusioned British public opinion. The same war saw the rise of the Wicklow-born journalist, Edwin Lawrence Godkin (1831-1902), who reported from the Crimea for the New York Times and Daily News (London). Later moving to the United States of America, where he founded and edited a number of titles, Godkin campaigned against slavery during the Civil War and the corruption of Tammany Hall-era local government in New York.

Pic: Sir William Howard Russell

Other Irish war correspondents included James David Bourchier (1850-1920), who reported from the Balkans in the 1880s for the London Times; Emile Joseph Dillon (1854-1933), the Daily Telegraph’s Moscow correspondent from the 1880s until 1903; George Lynch (b. 1868), who covered the Boer War for the Illustrated London News, as well as reporting on the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Russo-Japanese War, and the 1905 Russian Revolution; Stephen McKenna, who headed the New York World’s Paris office in the 1920s; and David McGowan, Russian correspondent around 1905-6.

While war reporting was, and remains, a largely gendered profession, with men dominating its ranks, a number of women reporters have made significant contributions to the development of this trade, such as Martha Gellhorn (Spanish Civil War) and more recently the Sunday Times correspondent Marie Colvin, who died in a rocket attack in Syria in 2012. However, the pioneering female war reporter was Kathleen Blake Coleman (née Ferguson) (b. c. 1864), a Galway-born woman who moved to Canada in her early-20s and reported on the Spanish-American War in the late-1890s, becoming the first accredited female war correspondent.

Pic: Galway-born Kathleen Blake Coleman

The prominence of Irish men and women among international war correspondents in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries is striking, yet demands explanation. John Horgan suggests that while no single factor can explain this prominence, ‘it is possible that the nature of journalism, as a career path for which university education was not a necessary qualification, may be part of the explanation’. In his short analysis of Russell, Godkin and Lynch, Daniel Mulhall sees these men as being subsumed into a wider Victorian world: ‘their worlds were those of Fleet Street and the great international crises of the second half of the nineteenth century, in which Irish affairs…were invariably a sideshow’.

Further reading

James Horan, “The great war correspondent’: Francis McCullagh, 1874-1956’ in Irish Historical Studies, 36:144 (Nov. 2009).

Daniel Mulhall, ‘Men at war: nineteenth-century Irish war correspondents from the Crimea to China’ in History Ireland, 15:2 (Mar-Apr 2007).

Philip Knightley, The first casualty: the war correspondent as hero, propagandist and myth maker (1975; rev. ed. 1999; rev. ed. 2003).

Eisenhower in Wexford, 1962

BY EMMA EDWARDS

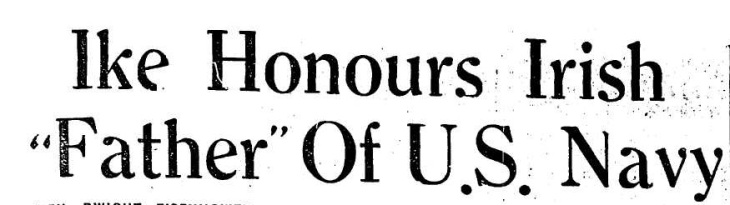

Headline in the Irish Examiner, 24 August 1924

The south-east tourist industry has reaped great currency out of the visit of an American president in 1963. However, what is perhaps less well known is that the visit of the 35th president of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, was preceded in 1962 by the visit of the 34th. Dwight D. Eisenhower was no longer a sitting president when he visited Wexford in 1962 but his visit emanated from a gesture of thanksgiving and commemoration during the course of his presidency. In 1956 a gift from the ‘people of the United States’ was unveiled on Crescent Quay, Wexford by President of Ireland Seán T. O’Kelly (who himself had married not one but two Wexford women from the nationalist Ryan dynasty, first Mary Kate and then following her death, her sister Phyllis). The bronze statue of Commodore John Barry was designed by William Wheeler and shipped to Ireland on board the U.S.S Charles S. Sperry. Barry, referred to as the ‘father of the United States navy’, was born in 1745 in Ballysampson, Tacumshane, Co. Wexford. Having gone to see as a child of ten he settled as a merchant sailor in Philadelphia and was a ship’s master by age 21. With the outbreak of the War of Independence, he offered his services to the Continental Army. His ship the Black Prince was outfitted for naval service, renamed the Alfred and became the first ship in the Continental Navy. Commissioned as a captain he led the first American capture of a British ship and received a personal note of gratitude from General Washington. With the foundation of the U.S. Navy in 1794 Barry, though listed as the senior captain of the service, bore the courtesy title of commodore (the position of commodore was not formally created until 1862). He died in 1803.

The visit of JFK to Ireland in June 1963 is considered an iconic event due to the president’s Irish ancestry, his viewing of the ‘Kennedy homestead’ in Dunganstown, New Ross and to the poignancy of his promise to be ‘back in the spring time’ with the shooting in Dealey Plaza a mere five months away. Eisenhower’s visit to Wexford was undertaken at less notice, fanfare and was bedevilled with setbacks. Eisenhower was due to make a tour of Europe in late summer 1962 when a visit to Ireland was discussed with the U.S. ambassador to Ireland. Wexford Corporation had to respond to charges from an aggrieved public and sceptical press that it had declined to receive Eisenhower. In a statement issued to the press, the Corporation claimed that ‘when the matter was first considered, the members genuinely felt that they could not do justice to such a distinguished person in mid-week.’ Eisenhower himself was also perturbed to learn that there was no airport close to Wexford. The Corporation decided to change its mind in response to ‘the wholehearted support they have now been offered from all sections of the community.’ Such support was expressed in erection of ‘We like Ike’ posters on the walls and streets of Wexford town, as reported by a journalist from the Irish Press. At a special meeting of Wexford Corporation on 16 August Alderman K.C. Morris expressed his hope that the visit would ‘clear up all the misunderstandings which had got wide publicity and should prove that Wexford at no time turned down the General’s visit’ and plans were put in place for Eisenhower’s helicopter to land on the G.A.A pitch two miles outside Wexford town. Eisenhower made quite literally a flying visit, arriving first in Dublin to stay in the Gresham Hotel and on the following day enjoying a luncheon with President de Valera. The former Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe arrived in Wexford on 23 August by helicopter to a town bedecked by bunting and a higher than average population of American tourists. Cheered on from streets and doorways, Eisenhower arrived to lay a wreath at the Barry Statue. He announced that he has been ‘a dismal failure’, explaining to a crowd soaked through by a torrential downpour that he had previously enjoyed a reputation for bringing fine weather with him. Gardaí and security men reportedly fought a losing battle with photographers. According to the calculations of an Irish Examiner journalist present, Eisenhower’s speech lasted less than two minutes in which he praised Barry as ‘a great patriot’ and then spoke to the Mayor of Wexford for four minutes, the latter also making a short speech. Whisked away for lunch in the Talbot Hotel, Eisenhower was back in his helicopter twenty minutes later. President Kennedy paid his respects to the Barry statue less than a year later giving Wexford Corporation further exposure to the executive branch of the U.S. government. Barry’s statue still stands on Crescent Quay looking out onto the Slaney estuary; other statues were erected in Franklin Square, Washington D.C. and at the entrance to Independence Hall, Philadelphia.

Further Reading

Irish Examiner, Irish Independent, Irish Press, Irish Times, Aug.-Sep. 1963.

David Murphy, ‘John Barry’ Dictionary of Irish Biography.

‘I personally don’t want to see another Ballymun again’: the lessons of urban planning and regeneration

Ballymun under construction, still taken from short video see (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3O7G8weRc98) (26 May 2016)

On the 10 May the master of the High Court, Edmund Honohan, speaking at the new Dáil committee on homelessness highlighted many of the lessons that can be learnt from the rapid construction of social housing projects without detailed planning stating: ‘I personally don’t want to see another Ballymun again’. Honohan was highlighting that the town had become a byword for the mismanagement of urban planning and management. Perhaps it is important as the state appears set on a new phrase of rapid construction of social housing to re-examine the history of Ballymun, to see what lessons we can learn from it and if those lessons are being implemented.

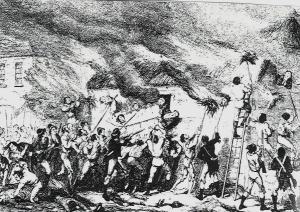

Ballymun was a direct response to a housing crisis which Dublin was experiencing in the 1950s and 60s. Dublin’s housing stock was not only under pressure from a rising population but also, in the city, extremely poorly maintained. Between the summer and end of 1963 tenements across the city collapsed or were evacuated due to safety concerns. House collapses in Bolton Street and Fenian Street led to the death of four people, forcing Dublin Corporation to adopt ‘emergency measures’ to deal with the crisis. These measures included the removal of over 1,000 people from homes deemed to be dangerous, leading to a doubling of the Corporation’s housing list.

The answer to the surge in housing demand quickly came from central government: pre-fabricated buildings. Such building techniques had become popular in Britain and Europe in the 1950s/60s and offered the government a relatively cheap and rapid way to construct homes. For some the use of such modern construction techniques and the introduction of high-rise living also signalled that Ireland was entering the modern age of public housing. Alongside the provision of spacious homes, constructed to high standards, the planners and government would meet the other needs of the new community, these included: shops, schools, green spaces, playgrounds, community halls and meeting rooms, a health clinic, a swimming pool and landscaped parks. It was to be a model of high-rise living, providing families with every amenity they required. However, as highlighted by Robert Somerville-Woodward, by the time construction began, in 1965, states across Europe were already abandoning such developments due to many of the problems that would scourge the new town, including poor maintenance of communal areas and the social isolation of residents.

James connolly Tower, available at Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_connolly_Tower_2007.JPG) (26 May 2016).

The first residents began arriving in the new town in 1966 and were delighted by the homes that greeted them. For many coming from inner-city tenements and others after years in cramped conditions on the Corporation’s housing list, the provision of three and four bedroom flats and houses, with central heating and hot water on demand, was warmly welcomed. However, while the homes were deemed adequate, the lack of facilities, many of which were incomplete even in the 1970s, led to the unravelling of the project. In particular, the town centre, to primarily consist of a shopping centre was not completed until after the completion of all the residential units, meaning that some tenants now housed miles from Dublin city-centre were literally years without access to shopping facilities. Added to this, the inclusion, and hence delay, of much of the town’s social facilities and a health centre as part of the new town centre further alienated the residents. Thus, when the town was formally taken over by Dublin Corporation in February 1969 it lacked much basic infrastructure that was essential for a properly functioning urban area.

By the 1970s the socio-economic demographics of the new town changed as more affluent tenants began to leave the area. This problem was exacerbated in 1985 by the introduction of the Surrender Grant Scheme. This scheme gave £5,000 to residents who decided to purchase their house, but as flats were not covered by the scheme many residents seeking to purchase their home sought transfers to houses. The scheme was an un-mitigating disaster for Ballymun, and in 1985 over 1,000 flats contained new tenants. This turnover of residents was to continue into the future and was in a large part responsible for difficulties creating a sense of community within the town. In tangent with this, many offers of housing in the area were declined, leading to the accumulation of a high percent of those from a social-economic deprived background or with substance abuse problems being housed there, by the 1980s the area suffered from a severe drugs problem.

Demolition of Séan MacDermott tower, available at Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MacDermott_Implosion.JPG#globalusage) (26 May 2016).

Despite, and perhaps because of, the difficulties that the community faced, many groups and organisations were formed to aid in the development of facilities and supports. These ranged from youth groups, to the establishment of a credit union, to other groups pushing for improvements in housing and the built environment. In the 1980s/90s a number of reports were commissioned to seek a way to solve the many difficulties that the town’s population faced. The results of these was the establishment of Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. in 1997, which was responsible for the demolition of all flat complex’s in the estate and their replacement with housing. The planners of the ‘new’ Ballymun would seek to address many of the failures of the original project. As well as the replacement of existing social housing, private housing would also be constructed to change the social-economic demographic of the area; schools would be upgraded; a new, modern shopping centre would also be part of the plans, as would a theatre and other recreational facilities. The area would be provided ample playgrounds and of extreme importance would be an investment in the human as well as the built capital of the area. A renewed focus on educational attainment and training would seek to improve not only the physical environment of the area but also provide greater opportunities to engage in the ‘Celtic tiger’. For this was truly a creation of that tiger, Ireland now had the money to correct the mistakes of the past, indeed break with the past, and what better way to demonstrate that the economic miracle was benefitting everyone than the erasure of those tower blocks that had come to signify the inequality of Irish society?

The regeneration of Ballymun has seen the demolition of all flat complexes and the construction of some of the promised facilities including a new swimming pool and the axis theatre. However, with the economic downturn much of the promised amenities have not been delivered. In particular, with the closure of Tesco’s in 2014, the shopping centre’s anchor tenant and one of the last remaining shops, Ballymun is again without a proper shopping centre. (The site of the new proposed centre remains vacate).

Thus, have we learnt the lessons of Ballymun? Like Edmund Honohan, the state has no desire to build large-scale social housing estates again. Rather the ideal for urban planners is a social mix, which house’s tenants from a range of social and economic backgrounds. This type of housing means that those engaged in anti-social behaviour will not become an overarching feature of any area; that amenities for the whole community can be funded by the community; that commercial enterprises, such as shops, will see the benefits of serving such communities. It is these lessons that the government and local authorities seem to have taken from the experience of Ballymun. But for residents of such large-scale social housing projects many of these lessons have been ignored during the recession. As can be seen in Ballymun, the lack of a shopping centre was deemed one of the central concerns of tenants arriving in the 1960s, and yet the same problem exists in 2016. Throughout the town’s existence external financial factors and economic downturn have affect the provision of services. This should be the primary lesson that we take from this case study: that short-term savings lead to long-term problems that are also much costlier to resolve.

Further reading

Robert Somerville-Woodward, Ballymun, a history (2 vol., Dublin, 2002) i & ii; see also Robert Somerville-Woodward, Ballymun, a history, Synopsis (Dublin, 2002), available at Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. (http://www.brl.ie/pdf/ballymun_a_history_1600_1997_synopsis.pdf) (20 May 2016).

Boyle M and Rogerson R J (2006) ‘“Third Way” urban policy and the new moral politics of community: A comparative analysis of Ballymun in Dublin and the Gorbals in Glasgow’ in Urban Geography, xxvii, pp 201-227, available at (http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/681/1/strathprints000681.pdf) (20 May 2016).

Ballymun regeneration Ltd., Sustaining regeneration: a social plan for Ballymun, available at Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. (http://www.brl.ie/pdf/SRBallymunLowRes_FA.pdf) (23 May 2016).

And for a look at the community’s view of the regeneration:

Ballymun Community Action Program (CAP), On the Balcony of a new millennium, regenerating Ballymun: Building on 30 years of community experience, expertise and energy (Dublin, 2000), available at (https://uniteyouthdublin.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/on-the-balcony-regenerating-ballymun.pdf) (20 May 2016).

Bio

Adrian Kirwan, co-editor of Holinshed Revisited, is an Irish Research Council funded Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. His research focuses on the interaction between society and technology, more about his research can be found here.

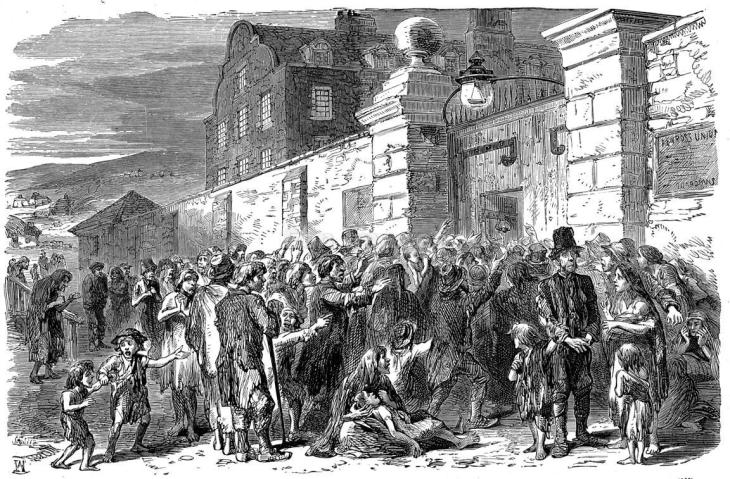

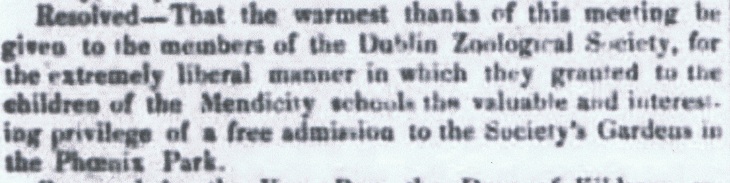

‘Enjoyment and great entertainment’ in nineteenth-century Ireland’s institutions

The geographic and social landscapes of nineteenth-century Ireland were significantly altered by the establishment of numerous institutions, largely aimed at confining, relieving and treating the deviant, destitute and sick poor. They ranged from prisons and bridewells, to lunatic asylums and medical hospitals; from houses of industry, mendicity societies and Poor Law union workhouses, to Magdalen asylums, industrial schools and reformatories. While numerous establishments (such as prisons and hospitals) dated from earlier periods, a significant upsurge was witnessed in the nineteenth century, reflecting a wider ‘institutional zeal’ (Cox, 2009) throughout the transatlantic world in this period.

Speaking broadly, these institutions are popularly associated with harsh and cruel regimes, untrained and uncaring staff, approaches to illness (especially mental illness) that lacked compassion, and conditions that bred disease and death. Perceptions of these institutions, and life within them, are generally negative. One question which has always fascinated me is the undeniable fact that in these harsh institutions where the lives of residents (staff and patients / prisoners / inmates) were subject to strict disciplinary regimes, there were moments of fun, laughter and joviality. I seem to recall Holocaust survivor Elia Wiesel’s account, in his Night, of a journey on a train to a concentration camp and his recollection of a young couple having sexual intercourse. Even in the direst of circumstances, aspects of life continue as before. Turning to Irish workhouses, asylums and other institutions, surely there were times when jokes were told, games were played by children, and people engaged in small, private acts of generosity and humanity. Of course, our understanding of the past is shaped by the surviving sources; for most of these institutions, the masses of poor patients / prisoners / inmates left behind few records of their experiences and thoughts. As such, what little understanding we can gain of their lives are filtered through the records, and perspectives, of the managers of these institutions.

In my work, on poverty, begging, and charity in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Ireland, I have caught glimpses of this aspect of life for the poor inside institutions. In those instances, the occasion for ‘enjoyment’ was organised by the managing committee / governors – such as a ‘feast’ – rather than a spontaneous experience of frivolity arising from the residents. This is most likely arising from the fact that the sources that provide these all-too-rare glimpses are usually the minutes and reports of the controlling body of the institution: an event was organised and recorded by the managing committee.

Seasonal treats were common in many institutions. In the premises of the Dublin Mendicity Society, a charity founded in 1818 to clear the streets of beggars, paupers were usually treated to a Christmas feast, in one instance being fed ‘roast beef and plum pudding’. The same Dublin charity also organised trips for its pauper children to the Zoological Gardens in the Phoenix Park, for ‘advantages of improvement and recreation’. Significant public events were also the occasions for treating the inmates of such institutions. In June 1838, the coronation of Queen Victoria was marked by Limerick Corporation ordering the first public illumination since Waterloo, as well as providing money to the city’s Mendicity Society and House of Industry ‘to provide the pauper inmates of these places the enjoyment of a comfortable breakfast and dinner, in commemoration of this event’. Two years later, to mark the marriage of Queen Victoria to Prince Albert, the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Ebrington, subsidised ‘an abundant dinner of prime ox beef’ for the ‘numerous mendicant poor’ in the Dublin Mendicity Society’s premises. This feast was complemented by the distribution of ‘180 saffron cakes…amongst the children of the [society’s] schools, being the gift of a member of the committee’. The royal marriage was also honoured in Clonmel, where the town’s mendicants ‘were supplied by subscription with 300 loaves of bread and 300lbs. of beef’. In March 1863 the Prince of Wales’s marriage was marked by ‘entertainment’ and ‘great enjoyment’ for 350 patients at the Richmond District Lunatic Asylum (Grangegorman) on Dublin city’s north-side. A rare insight from a patient’s viewpoint comes in a letter of complaint, composed by a patient of the Cork Street Fever Hospital, Dublin in 1816, wherein the patient (William McLoughlin of Wood Street) alleged that other patients bribed the ward nurses for the privilege of staying up late, drinking tea and singing.

Image: An 1830s newspaper notice, recording the visit to the Dublin Zoological Gardens of child paupers from the city’s Mendicity Institution

Contrary to the quip of a colleague who read this article, I am not suggesting that life in workhouses was fun! I believe that to highlight these (admittedly few) recorded instances is not to deny the level of suffering in such institutions, but, rather, to deepen our understanding of the varied experiences of those who lived within their walls, as well as the actions and motivations of those in control of these institutions.

Further reading:

John O’Connor, The workhouses of Ireland : the fate of Ireland’s poor (1995).

Audrey Woods, Dublin outsiders: a history of the Mendicity Institution, 1818-1998 (1998).

For a wider discussion of institutions in this period, see Catherine Cox, ‘Institutionalisation in Irish history and society’ in Mary McAuliffe et al (eds), Palgrave advances in Irish history (2009).

The Royal Irish Constabulary: centralised and ‘political’ policing in Ireland

Tack badge from the RIC Mounted Division

The policing of Ireland was a topic that vexed politicians from the act of Union, 1800, onwards. The country was prone to disturbances ranging from that particularly Irish pastime of faction fighting to agrarian unrest. In the opinion of Robert Peel, undersecretary at Dublin Castle, the provision of law and order by the country’s ‘natural’ leaders, meaning local landowners, had broken down. However, difficulties with policing spread beyond local notables to the county constabulary. These forces were controlled by local magistrates, appointed by the grand jury and were generally considered worthless.

The situation led to an ongoing struggle between local landowners and Dublin Castle, as the central administration attempt to reform policing and the administration of justice throughout the island. The outcome of this was the eventual establishment of a centrally control nation-wide police force in 1836. The Irish Constabulary (the Royal prefix would be awarded in 1867, following the force’s efforts in suppressing the Fenian rising of that year) was formed in 1836.

The government’s efforts to centralise the RIC was in direct response to the divided nature of Irish society. While the natural leaders of local politics were predominantly Protestant, the vast bulk of the population were Roman Catholic. While we must be careful not to simplify the divisions between these communities, there were two completing political and religious camps on the island. Due to this, any decision by government or its arms, such as the police, would be scrutinised for partiality. Given the formation of the Irish Constabulary only seven years after the granting of Catholic Emancipation, by a tory government reliant on the support of O’Connell, fears of centralised (political) policing were rife. Indeed such centralised policing was contrary to British ideas of liberty; the ideal was a non-military, regional police force whose control was in local hands. The RIC had more in common with European models of policing than British. Indeed, its intelligence gathering activities were more akin to policing in Indian than Britain.

By having a centralised police force throughout most of the island (the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) was responsible for policing in Dublin) the Irish administration at Dublin Castle sought to ensure that police actions did not incite conflict. Hence, fears of political policing were in a manner well founded. Thus, it was Ireland’s well-known uniqueness in terms of political and social unrest that convinced the government of the need for a centralised and ‘politically’ controlled police force. This was to have long-term impacts on the structure of policing in Ireland, leading to a high level of correspondence. The police force was to become a sort of unofficial civil service. It was to compile statistics on a range of subjects, ranging from farming outputs to surveillance. However, this centralisation also removed the freedom of action of local commanders, leading, in many cases, to the most mundane decisions being taken at high levels of the force’s command structure.

Further Reading

Galen Broeker, Rural disorder and police reform in Ireland, 1812-36 (London & Toronto, 1970).

Stanley H. Palmer, Police and protest in England and Ireland, 1790-1850 (Cambridge, 1990).

Margaret O’Callaghan, ‘New ways of looking at the state apparatus and the state archive in nineteenth-century Ireland “curiosities from that phonetic museum”: Royal Irish Constabulary reports and their political uses, 1879-91’ in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, civ, C, no. 2 (2004), pp 37-56.

Bio

Adrian Kirwan, co-editor of Holinshed Revisited, is an Irish Research Council funded Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. His research focuses on the interaction between society and technology, more about his research can be found here.

The Aud and Karl Spindler; Good Friday 1916

By David Gahan

With events commemorating the Easter Rising expected to reach a high point in Dublin this weekend, aspects and events surrounding the Rising are rightly being looked at from various angles. The story of the Aud, its captain, crew and cargo of arms is one such aspect of the 1916 narrative and a chance discovery of some text from a talk given by Karl Spindler, captain of the Aud added some new insights to this story.

The story of the Aud is often overshadowed by the landing of Roger Casement from a German U-boat, on the Kerry coast on the same day and his subsequent arrest, imprisonment and execution in August 1916. The background to this is the efforts of Clan na Gael in America and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Ireland to secure an arms shipment from Germany to help stage an insurrection in 1916. John Devoy, a Clan na Gael leader had numerous meetings with members of the German Consulate in New York, including Franz von Papen, to help facilitate this operation. Casement was already in Germany to further this and pursue his plan of raising an Irish Brigade from Irish prisoners of war, though Devoy was sceptical of this and wary of some of Casements plans. Robert Monteith was also sent by the Clan to Germany. In early March Devoy received word that a ship with 20,000 rifles and ammunition would arrive in Tralee Bay on the morning of 20 April, Holy Thursday. But on 14 April Devoy received a hand delivered message from Ireland that the arms must not be landed before Easter Sunday night. This spelt disaster for the operation as the Aud which had no wireless on board, was already on its way to Ireland to rendezvous on the agreed date.

Karl Spindler relates how he was tasked with choosing twenty-one men for an expedition of which he did not know the plans; was given command of a ship, the Libau and that arms were loaded onto it in Lübeck. Here they realised this was not a normal wartime operation when they changed from German uniforms into common dungarees. The ship was provided with official papers and ‘became’ a Norwegian vessel, the Aud. The efforts to disguise the ship were meticulous, the crew were ordered not to shave and to walk about with their hands in their pockets while in the view of other ships. Norwegian newspapers and books were provided, pictures of girls and letters were put up all over the ship, in cupboards etc. The crew could not speak Norwegian but were to speak in low-German if encountered by the British in an attempt to disguise their nationality. Spindler even bought a dog in Lübeck to have on board, ‘every sailor knows that every tramp steamer has a dog’ and he was to be visible if enemy ships were passing.

Through skilful navigation and planning Spindler managed to steer the Aud through four British blockades. At four o’ clock in the afternoon, 20 April, they reached their rendezvous point, Innistooskert Island in the middle of Tralee Bay. They waited until noon on Good Friday for some signal from the shore which was not forthcoming, then with a British patrol boat approaching them they left the bay but later that evening were surrounded by British ships and instructed to proceed to Cobh. The next morning as the Aud entered Cobh, the crew raised the German Ensign and scuttled the ship.

Though part of the German planning was precise, to send a ship without a wireless and the make-up of the cargo, fifteen-year-old Russian rifles that had been captured on the Eastern Front, raises some doubt over their commitment to the expedition.

Casement had been put ashore on Good Friday, but weak from sickness and the exertions of rowing to dry land was left at McKennas Fort, Banna Strand while his comrade Monteith sought aid. Casement was captured some hours later; Monteith remained on the run for eight months before a passage was secured returning him to America.

These events happened in Kerry and off the South-West coast on Good Friday/Easter Saturday, one hundred years ago.

Bio:

David Gahan is a final year Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, Maynooth University.

The Dublin telescope makers and the empire: a short history of Grubbs

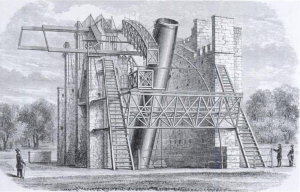

Great Melbourne Telescope, 1869, available at WikiMedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Melbourne_Telescope_1869.JPG?useland=en-gb) (23 March 2016).

Thomas Grubb was born to the Quakers William Grubb and his wife Eleanor (née Fayle) in 1800. Around 1832 Grubb established a mechanical engineering workshop in Dublin and began constructing modest reflector telescopes for his own use. Through his interest in astronomy he began undertaking various commissions for the erection and construction of telescopes, including a fifteen-inch reflector for the Armagh observatory. In order to mount this large telescope Grubb designed a system of triangle levers to reduce stress on the mirror. A similar system was employed by William Parsons, third earl of Rosse, in the construction of his six-foot reflector, ‘the leviathan’, at Birr Castle in the 1840s. In this early period Grubb’s work was primarily funded by private individuals.

These commissions soon brought him to the attention of scientific figures throughout the United Kingdom, and he was hired to construct telescopes for the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, and the University of Glasgow. He also fabricated twenty sets of magnetometers for Professor Humphrey Lloyd’s (Trinity College, Dublin) efforts to establish a network of magnetic observatories throughout the British Empire. These were to further scientific understanding of geo-magnetism and, eventually, thirty-three observatories were set-up throughout the world on the same model as the magnetic observatory based in Trinity College, Dublin.

A great deal of this research was not driven by ‘pure’ scientific interest. The British state, as a maritime nation, was strongly motivated to fund astronomy and the production of star charts. In fact, George Airy, Astronomer Royal, saw the main tasks of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, as producing accurate stellar and planetary maps and the regulation of ships chronometers, all essential for navigation. Thus, the successful trajectory of Grubb’s business was, in many ways, firmly tied to wider British Imperial and trading interests. As the nineteenth century progressed the British state was to begin funding ‘pure’ research to a greater extend and this was to provide Grubb with much work.

It was the success of the Rosse telescope, which had gone someway to answering the question of the resolvability of nebulae, that was to prompt calls for a similar telescope to be erected in the southern hemisphere. This was realised in 1869 when a four-foot Grubb reflector was installed in Melbourne. Unfortunately, this telescope was to be a resounding failure, probably due to the inability of staff in Melbourne to polish the mirrors (these had been made using polished metal instead of the silver-on-glass method that was becoming popular). Thomas Grubb was to die in 1878 but the company was to remain in operation under the guidance of his son, Howard, who had taken control in 1868.

Howard Grubb was to remain in charge for fifty-seven years and in this time constructed most of the large telescopes erected across Britain and its empire, including five for the Royal Observatory. In addition, the company also constructed telescopes for a number of others, including a twenty-seven-inch reflector for the University of Vienna, 1881. In this period the majority of Howard’s large instruments were refractors. In the closing years of the nineteenth century the company also began making photographic instruments for astronomical observations. The previous system of human observers sketching their observations had been open to error and encountered difficulties when attempting to draw large and detailed star charts. In 1890 the company delivered seven, of thirteen, such instruments that were used as part of the Carte du ciel (map of the sky) project, the rest were constructed by the Henry brothers of France. (It was on one of these Grubb telescopes that Arthur Eddington was to show the distortion of a star’s position when its light passed near the sun, thus providing the first proof of Einstein’s theory of relativity).

In the twentieth century the company was to put its optical expertise to military use, designing rangefinders, gunsights and the first submarine periscope. This was to tie the fortunes of the company to the state in an even more obvious manner. Due to its increased importance to the war effort, the company transferred to the south of England in 1918. This move was to prove decisive and, with the end of the First World War, Grubb was unable to meet increasing costs. The firm was sold to Charles Parson, the youngest son of the third earl of Rosse, in 1925 and the new firm, ‘Sir Howard Grubb, Parsons and Co.’ was to continue in operation until 1985.

Further reading

Ian Elliott, ‘Grubbs of Dublin: telescope makers to the world’ in Juliana Adelman and Éadaoin Agnew (eds), Science and technology in nineteenth-century Ireland (Dublin, 2011), pp 47-62.

Anita McConnell, ‘Scientific instrument makers’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2015), available at (www.oxforddnb.com) (19 Mar. 2016).

John Burnett, ‘Grubb, Thomas, engineer and telescope builder’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2015), available at (www.oxforddnb.com) (19 Mar. 2016).

Bio

Adrian Kirwan, co-editor of Holinshed Revisited, is an Irish Research Council funded Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. His research focuses on the interaction between society and technology, more about his research can be found here.

MUSEUM OF THE MONTH: Anne Frank House, Amsterdam

BY EMMA EDWARDS

As a historian I always feel a rush of gratitude for those diarists who maintained such painstakingly detailed and regular entries. Some diaries are preserved self-consciously for posterity; others avoid destruction or oblivion through good luck or meticulous care, only for the value of their contents to become apparent through chance investigation, donation or publication. Diaries are not, as few if any historical sources can be, objective, unbiased or comprehensive. Yet just as historical commentary is shaped by the perspective of the historian, diaries provide a fascinating insight into the perspective of one individual on wider historical events: perspectives that can be representative or completely unique. This intersection of the personal with the political lends greater colour to the narrative and reminds us that history is not just something that happened, but something that people actually lived.

In terms of diaries of historical significance, the diary of Anne Frank is arguably the most famous and certainly most widely read. As such I could not pass up on the opportunity to visit a monument to her experience and to the first primary source I had ever read as a child. Anne Frank House (Prinsengracht, Amsterdam) seeks to document Anne’s experience as a microcosm of the persecution of Dutch Jews and (as in the case of Anne’s family) of German Jews whose exodus to other European cities such as Amsterdam did not count on Hitler’s Blitzkrieg of 1940 and the extension of Fortress Europe to the Netherlands. As you enter the exhibition, context is provided on the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam and the anti-Jewish laws introduced after 1940. Documents are put on display in a space renovated in the 1990s to recreate the original front of the building, including the warehouse and offices of Opekta, Otto Frank’s business, licensed to sell pectin, the gelling agent necessary for jam making. The museum documents the gift of Anne’s diary and her cherished ambitions to be a writer. Text from its pages are used to narrate Otto’s decision to hide his family in unused rooms (the ‘secret annex’) in 1942 with the help of office staff while keeping it a secret from warehouse staff. Visitors travel up to the ‘secret annexe’ behind a bookshelf (the original bookshelf is on display) to enter the hiding place. Again excerpts from Anne’s diary are used to evoke the strained atmosphere of the annex with the Franks sharing the small space with another family, the van Pels, and a dentist, Fritz Pfeffer. Anne’s own sleeping space has been preserved and on display are copies of her posters of movie stars and the young Princess Elizabeth.

The visitor makes their way into a museum space that provides a sober reflection on the fate of the Franks, whose hiding place was stormed by the Security Police on 4 August 1944. Of the eight people in hiding only Otto Frank survived-he was in Auschwitz for its liberation. Short video clips provide first-hand accounts of the concentration camps, including an interview with a friend of Anne’s who met Anne in Bergen-Belsen only a few short weeks before her death. Another of the museum’s rooms reflects on the impact of Anne’s diary, preserved by Opekta office worker Miep Gies who returned it to Otto for it to be subsequently published in seventy languages. A manuscript version can be viewed in the museum. I was really interested to learn that in the months before the arrests, Anne had been editing and revising her diary and working on a novel The Secret Annex. This certainly prompts me to reflect on how much diarists consider if and how their personal entries will be preserved and received by posterity. The exhibition is a triumph of simplicity, in allowing the force and poignancy of the diary to be presented with the minimal intervention of audio-visual material that so often proliferates and which can, in some cases, distract from the contents and missions of museums. The curators thankfully resisted the urge to include too much material in the secret annex space which allowed them to successfully evoke the stark reality of two years of claustrophic confinement.

In terms of practicalities Anne Frank House is located quite close to the centre of Amsterdam and is easy to find via many of the tram lines. Booking a ticket in advance is strongly recommended as queues can reach epic lengths; however the museum staff do an excellent job of ensuring the small space does not become too crowded.

See: http://www.annefrank.org/en/Museum/Practical-information/

‘Zealous friends’: challenges for historians of the language of charity

Negotiating changes in the meaning of words is a frequent challenge for historians. When consulting primary sources, one is reading, interpreting and transcribing words as they were used in a given period from the past; it is in the context of that period that the words must be understood. Yet, the historian may then use the same words in his/her own analysis (that is, in the secondary source). This can present a challenge for the reader of the historian’s subsequent published work.

This was demonstrated to me recently at a session at the annual conference of the Irish History Students’ Association in NUI Galway. The session focused on ‘Shades of Roman Catholicism in Ireland, 1844-1950’. One speaker presented an excellent paper on Catholic charity in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Dublin and, not surprisingly, the word ‘zeal’ was regularly referenced, in quotations from primary sources. It struck me as interesting because just moments later, in another excellent paper, the next speaker, in her interpretation of Catholic missionary work, described some historical figure as being ‘over-zealous’, which implied some manner of negative connotations.

This linguistic irregularity caught my attention as ‘zeal’ is a word that I have had to negotiate in my own research into charity and philanthropy in nineteenth-century Ireland. Charitable works in this period were driven by religious influence and defined by confessional identity. This was a period of spiritual and devotional revival in both Catholic and Protestant Europe, and the Irish manifestations of these revivals were marked by localised nuances. Much of my research in recent years has focused on the responses of charitable societies and denominations to poverty and beggary, and the word ‘zeal’ commonly appears in the primary sources. However, where it does appear, ‘zeal’ had positive connotations; for instance, a person’s obituary would note the individual’s ‘zeal’ to undertake philanthropic work, set against the ever-constant backdrop of religious inspiration. ‘Zeal’ was used to describe a person’s dedication to furthering the spiritual well-being of others, particularly the distressed, marginalised and irreligious. Any study of the language of charity – the best Irish example being the work of Margaret Preston – will inevitably come upon the use of ‘zeal’ in contemporaneous sources. For instance, in the evangelical Christian Examiner magazine in 1829, the rector of Powerscourt, Rev Robert Daly, a fascinating figure for his views on poverty and poor relief as much as for his influence during the ‘Second Reformation’, praised the evangelical wing of the Church of Ireland as follows: ‘To their zeal, devotedness, piety, and practical usefulness, I believe the church is indebted for the place it now holds in public opinion…’ The praising of one’s ‘zeal’ was cross-denominational and, in my own research, appeared most frequently in sources pertaining to Catholic female religious communities, particularly in obituaries for deceased members of orders and congregations. One Presentation Sister was remembered after her death as exerting ‘a most persevering zeal for the instruction of poor children’, while following the death in 1818 of Sister Mary Teresa (Catherine Lynch), the Sisters of Charity lamented that ‘the poor have lost a zealous friend, and the community a striking example of religious virtues’.

(‘On Zeal’ in Methodist Magazine, vol. 21 (May 1798))

The significance of this is that in today’s parlance ‘zeal’ often carries negative connotations. Religious zeal is associated with fundamentalism and intolerance, and is regularly used in an accusatory sense. Yet, among charity workers and philanthropists in the nineteenth century ‘zeal’ was a benevolent motivating force, as captured in an evangelical Methodist publication from 1798: ‘It is the SPIRIT of CHRIST infused, with a sense of his love, into the heart; it is a generous philanthropy and benevolence, which, like the light of the Sun, diffuses itself to every object, and longs to be the instrument of good, if possible, to the whole race to mankind.’ Historians negotiating words such as ‘zeal’ must be cognisant of what these terms meant to those who used them in the past (in the primary sources) and what they mean to readers of their own work (secondary sources).

British social reformers in nineteenth-century Ireland

In researching the history of poverty and charity in pre-Famine Ireland, I have been struck by the constant flow throughout Europe and the Atlantic world of ideas of moral and material improvement. Philanthropists and social reformers, either acting in an individual capacity or as part of a corporate entity (such as a charitable or intellectual society), regularly exchanged correspondence with colleagues in other countries, in which they shared their experiences and ideas of poor relief, medical treatment and education initiatives, to name but a few areas of interest.

Furthermore, many individuals travelled abroad extensively, gaining a first-hand insight into the work of other philanthropists. Many of the leading British social reformers in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries travelled to Ireland, visiting various institutions and meeting contacts among the philanthropic urban middle classes. The value of travellers’ writings has long been appreciated by historians, from Constantia Maxwell’s work in the 1940s and 1950s, to Christopher Woods’s recent guide to travellers’ accounts as source material (published in the Maynooth Research Guides to Local History series). What attracted many of these social reformers to this island was the impression that Ireland was a distinctive place on the fringes of Europe, singularly afflicted by poverty and moral decay. As Niall Ó Ciosáin has argued in his most recent work (Ireland in official print culture), the tropes of social conditions in Ireland being indescribable and unimaginable, and worse than those anywhere else, were well established in contemporary discourse. These motifs are to be found in the reported proceedings of parliamentary debates and inquiries, public sermons, and reports of social reformers. Having noted this trend, it is useful to briefly identify just some of these individuals, whose influence was international and who visited Ireland at some point in this period:

Elizabeth Fry (née) Gurney (1780-1845), penal reformer and philanthropist. By the time she travelled to Ireland in 1827, Fry was already a noted campaigner for prison reform, particularly in the incarceration of women and children. During her three-month visit to Ireland in 1827, Fry and her brother (Joseph John Gurney) visited around forty welfare and custodial institutions throughout the country – prisons, lunatic asylums, mendicity asylums, houses of industry. They co-authored a report to the Lord Lieutenant on their inspections of these institutions.

Caption: Quaker Elizabeth Fry, who drove prison reform in early-nineteenth-century Britain and Ireland

Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), educationist in London. The Lancaster model of education was based on the monitoring system, whereby older pupils (monitors) taught the younger pupils, overseen by an adult master. His educational reforms proved influential and were adopted by the Kildare Place Society, whose founding meeting in Dublin in 1811 was attended by Lancaster. Lancaster visited Ireland on a number of occasions and was a popular public speaker; a lecture in Drogheda in 1815 was attended by a reported 1,500 people.

Robert Owen (1771-1858), philanthropist and industrialist. Owen is best known for establishing the town of New Lanark in Scotland, centred around his cotton mill enterprise. His enterprise was marked by reduced working hours and improved housing for employees, and the provision of infant education. Owen’s tour of Ireland lasted from October 1822 to April 1823, a period of famine in western Ireland and during his visit, Owen visited many distressed areas. Throughout the country, he held public meetings, at which he promoted his ideas for planned communities. Two years later, Owen gave evidence to a parliamentary inquiry into poverty in Ireland and his New Lanark model was implemented at Ralahine, County Clare in the early-1830s.

Caption: Robert Owen, whose planned industrial town at New Lanark (right) inspired a similar experiment at Ralahine, County Clare.

Rev. Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847), Church of Scotland minister and social reformer. Chalmers was perhaps the most well-known and influential public intellectual in the first half of the nineteenth century. In St John’s parish in Glasgow, he pioneered a poor relief scheme based on house-to-house visiting of the poor and voluntarism in the provision of assistance. Chalmers travelled to Ireland on a number of occasions, being regularly invited by Irish ministers to deliver charity sermons, in the knowledge that Chalmers would attract large crowds of donors. In advance of his sermon at the opening of the Fisherwick Place meeting house in Belfast in 1827, members of the public were advised that only ticket-holders would be admitted, given the demand for places.

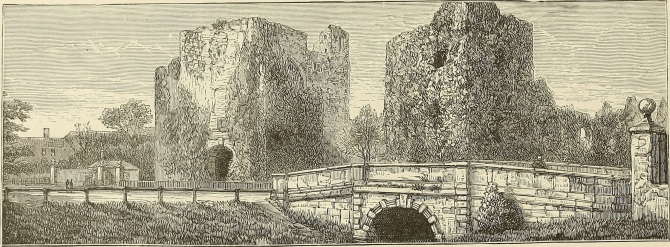

Book review: Fergal Donoghue, Crime in the city: Kilkenny in 1845 (Dublin, 2015)

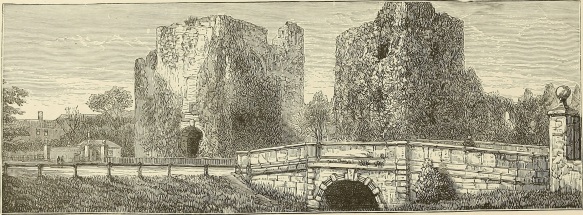

MAYNOOTH CASTLE IN 1885, AVAILABLE AT WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (HTTP://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:MAYNOOTH_CASTLE_1885.JPG) (ACCESSED 6 FEB. 2015).

On the 10 September the latest books in the Maynooth Studies in Local History series were launched at Maynooth University. This series -edited by Professor Raymond Gillespie and published by Four Courts Press- has been producing valuable local history studies since 1995 and has accumulated a total of 122 pamphlets. These cover a broad geographic spread across the whole of Ireland. The pamphlets normally focus on a particular aspect of their respective area’s history. They offer an informative, enjoyable and accessible insight into the history of selected local areas. Of particular worth is the ability of the series to connect the local to the national and demonstrate how wider national trends played out in a local setting. In addition, the relatively short nature of these publications means that they are ideally suited to those with little time on their hands.

This year six books were published, namely: Gerard Dooley, Nenagh, 1914-21: years of crises; David Doyle, The Reverend Thomas Goff, 1772-1844: property, propinquity and Protestantism; Adrian Empey, Gowran, Co. Kilkenny, 1190-1610: custom and conflict in a baronial town; Pierce A. Grace, The middle class of Callan, Co. Kilkenny, 1825-45; Ann O’Riordan, East Galway agrarian agitation and the burning of Ballydugan house, 1922; Fergal Donoghue, Crime in the city: Kilkenny in 1845.

Typical of the high calibre of the series is Fergal Donoghue’s Crime in the city: Kilkenny in 1845 (Dublin, 2015). The book provides a fascinating insight into the nature and punishment of crime in Kilkenny city in 1845. The book begins by providing much context in terms of the social condition of the city in the period. It demonstrates that well-known generalisations such underemployment and the lack of a wage economy created a significant underclass in the city. In doing so the book also highlights the conditions in which this underclass lived. The author is also careful to guide the reader through the nuances of the locality and demonstrates that there were two sides to the city: one living in poverty alongside another living in relative wealth. The second chapter places justice and punishment in the city in a national context and gives the reader a good understanding of how the justice system in the Kilkenny operated in 1845.

The final chapter of this short book is a testament to the great efforts of the author to garner as wide a picture of crime and its punishment in the city as possible. The author demonstrates not only the effects of the famine on crime in the city but also through careful and insightful analysis of the statistics highlights how the study of sentences can provide an insight into the fears of the city’s elite.

Overall this short book offers a fine contribution to not only our understanding of crime and punishment in Kilkenny city but also to the wider national history of this subject. In doing this the author provides a valuable insight into the motivations and fears of those responsible for the punishment of crime in mid-nineteenth century Ireland.

This book (priced €8.95) and the rest in the series are available via the Four Courts Press website at: http://www.fourcourtspress.ie/books/browse/history/maynooth-studies-in-local-history/

Bio

Adrian Kirwan, co-editor of Holinshed Revisited, is an Irish Research Council funded Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. His research focuses on the interaction between society and technology, more about his research can be found here.

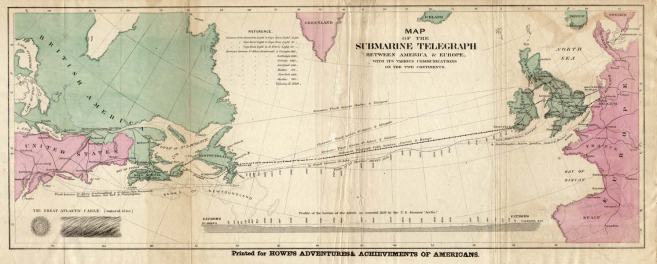

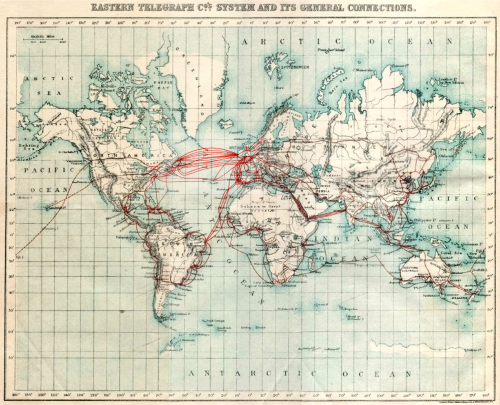

The first transatlantic telegraph cable

Map of submarine cable between America and Europe (1858), in Howe’s Adventures & Achievements of Americans, available at Wikimedia commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atlantic_cable_Map.jpg?uselang=en-gb) (21 Aug. 2015).

The recently approved €300 million transatlantic fibre optic cable to connect Mayo and New York will now doubt provide an important communication link between the US and not just Ireland but also the rest of Europe. While there is always an element of risk with such infrastructural projects, this one can build on a history of transatlantic telecommunications technologies going back to the mid-nineteenth century. The first attempt to construct a telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean was to take place between 1857-8. Given the fact that the first submarine telegraph cable had been laid only seven years before, between Britain and France, the scale of ambition must have been obvious to contemporaries.

However the story of this first cable attempt started much earlier. In 1854 the American financier Cyrus Field backed the construction of a telegraph line that would connect St. John’s, Newfoundland, to the rest of North America’s telegraph network; this line would be completed in 1856. As the distance from here to the British Isles was c. 1,000 miles shorter than from New York, the new cable could seriously impact on the time taken to transmit intelligence across the Atlantic and shorten the length, and hence expense, of any such cable. Such a crossing would benefit from a natural deep-sea plateau, which would mean that the cable would not have to descend too deep, and, unbeknown at the time, would protect the cable from the mid-Atlantic ridge.

In 1856 Field reached an agreement with John Watkins Brett (who had be responsible for the laying of some of the early telegraph submarine cables) and Charles Bright (the chief engineer of the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company (B&I MTC)) to form the Atlantic Telegraph Company. A high proportion of the company’s shares were bought by directors of the B&I MTC, the chairman of which was Charles’s brother Edward Bright.

The first order of business for the new company was to secure some type of funding from the government. Despite the prevailing laissez-faire ideology, trade with North America was significant and the development of a rapid means of communication would no doubt be of benefit to the British economy. Due to this reason the government agreed to provide ships and the expertise needed to take soundings of the ocean floor, lay the cable and, most importantly, it agreed to subsidise the company’s operations up to the sum of £14,000 for as long as the cable was operational.

The cable having been constructed by the Gutta Percha Company was sent to Glass, Elliot & Co. and R.S. Newall & Co. for the addition of armour (this involved the wrapping of metal wire around the cable to protect it from damage by the ocean floor or anchors of ships). In 1857 this cable was loaded on the British government-supplied HMS Agamemnon and the US government-supplied USS Niagara. The presence of these two ships highlighted that the success of the cable was very much in the interests of both governments and that both were willingly to intervene in private enterprise when it was deemed necessary for the welfare of the state.

Unfortunately the 1857 attempt failed due to technical difficulties, the apparatus for feeding the cable over the edge of the ship failed. The following year however a second, successful, attempt was made. Much fanfare greeted the successful laying of the cable and telegrams were exchanged between Queen Victoria and President James Buchanan. However, within a short period of time it was obvious that the cable was not operating effectively and it was to fail completely in October 1858.

It failure was to be a turning point in the development of telegraphic technology. While prior to this telegraph engineers and electricians were primarily responsible for the design and construction of cable and apparatus, the failure and momentous expense of the transatlantic cable lead to the establishment of a parliamentary committee in Britain. This in turn called upon the expertise of many in the scientific communication, including the future Lord Kelvin, William Thomson. The effect of this was to put telegraphy on a much more scientific footing. Thus, while debates between engineers, who viewed electricity on a similar manner to fluid in a tube, and scientists who wanted to establish themselves as the experts on these technologies were to continue, the failure of this cable helped the scientists to promote their position as the dominant force in the development of electrical technologies.

Further Reading

Anton A. Huurdeman, The Worldwide History of Telecommunications (New York, 2003).

Bio

Adrian Kirwan, co-editor of Holinshed Revisited, is an Irish Research Council funded Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. His research focuses on the interaction between society and technology, more about his research can be found here.

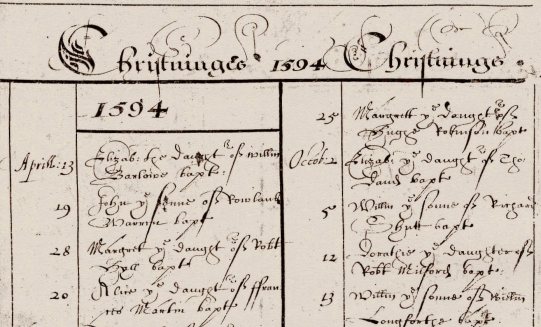

Resources for Historians: Catholic Parish Registers at the National Library of Ireland

The National Library of Ireland’s (NLI) digitalisation of Catholic Parish Registers is an encouraging example of how technology can both stimulate and satisfy the genealogical interests of the Irish public. Populating the branches of the family tree that stretch further back than the 1901 Census can often prove to be a challenging and onerous task. The first full government census of Ireland was carried out in 1821, followed by censuses every ten years thereafter. It is a tragedy for Irish genealogy that the pre-1901 records of the Registrar General of Births, Deaths and Marriages have been decimated by the intervention of various unfortunate events and decisions. While the returns for 1861 and 1871 were never preserved for posterity, the census data for 1881 and 1891 was obliterated when the records were pulped during the First World War, possibly due to a shortage in paper. The returns from 1821-1851 were, famously, almost completely destroyed in the fire that engulfed the Public Record’s Office in 1922 in the early stages of the Civil War.

Consequently, arguably one of the best, if not the best, source of general data on individuals living in nineteenth century Ireland is the Catholic Parish Registers. The NLI holds a vast microfilm collection of Catholic parish registers on microfilm and has recently completed the project of digitalisation whereby the microfilm pages were scanned and uploaded as images to be perused on the NLI’s website. In fact the project is arguably the continuation of efforts that began as far back as 1949 when the NLI offered its services to the Catholic hierarchy to ensure the permanent preservation of parish registers. An NLI staff member was duly dispatched to every diocese and over a period of twenty years (with additional filming of some Dublin registers in the 1990s) the NLI developed microfilm copies of over 3,500 registers from 1,086 parishes in Ireland (North and South) with some records stretching back as early as the seventeenth century. Now, approximately 373,000 digital images have been uploaded to the NLI’s website.

To search the records, the NLI has provided a user-friendly format, whereby the researcher reviews a map of Ireland, divided by county. Simply click on the county you are interested in, e.g. Wexford, and you will be immediately presented with the various parishes (in this example, from the Diocese of Ferns). Select your parish, e.g. Wexford (town) and you will be brought to the various digitalised microfilm copies of the original registers. The microfilm is arranged by time period and you can peruse records of births or marriages. Some of the very early registers can be that more difficult to decipher and appear to be a little damaged and perhaps watermarked, thus justifying the timely intervention of the NLI over sixty years ago in making permanent copies of the registers before their details were lost forever. However as researchers and historians the digitalised microfilmed images can allow us to experience that evocative thrill of studying our ancestors, in the handwriting of a near contemporary who preserved, for posterity, the beginnings and the most significant moments in their lives.

Begin researching:

Further reading

http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/help/history.html

Free workshop at the Royal Irish Academy: Teaching and learning using the Irish Historic Towns Atlas at third level

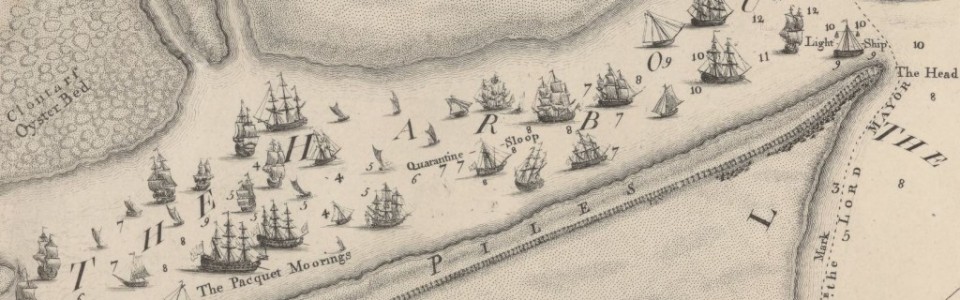

Academy House, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2. Date: Thursday 10 September, 09:30-16:30

This is a one-day workshop aimed at those who are either currently or intending to use the Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA) as a tool for teaching at third level. Those regular readers of this blog will know that the IHTA is an ongoing project of the Royal Irish Academy which aims to trace the morphology of towns and cities through time and space. The projects has completed a number of towns and cities, of varying sizes, throughout the island of Ireland, thus, proving extremely useful for the comparative study of the development of urban centres. Each atlas consists of a number of useful maps on the development of these towns. It also contains a valuable topographical gazetteer which allows the researcher to trace the purposes to which various sections of the town were being used through time. The gazetteer –which is divided into various sections- can also help in understanding how various social aspects of the city, such as religion, impacted on the built environment. This means that each atlas can also provide an important tool for the student to investigate the development of individual urban centres.

At the heart of the atlas project is its reliance on primary sources. This allows students, very early in their studies, to access a wealth of information based on primary source material. It also provides a staging post from where students and teachers can explore the usefulness of the topographic and cartographic record while broadening their understanding of the need to explore other material to gain a fuller picture of the historic urban centre and the society which inhabited it.

This workshop would appeal to individuals across a range of disciplines including history, geography, local studies, archaeology and digital humanities. The workshop is open to not only lecturers but also to third-level tutors, demonstrators, heritage professionals and anyone who would like to be exposed to new tools and methods for teaching. It is presented as an opportunity for discussion and debate about the uses the atlases can be put to and it is hoped that this will feed back into the general atlas project.

With a board range of talks from some well-known and respected researchers and lectures in various fields this promises to be not only an interesting and informative day but also the start of a period of expanded use of the atlas as a tool for third-level teaching.

For more information and registration go to: http://ria.ie/Events/Events-Listing/Teaching-and-learning–using-the-Irish-Historic-To

Or click on the file below:

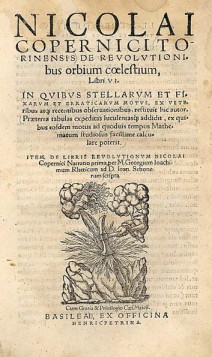

Conference review: the British Society for the History of Science, Swansea University, 2-5 July 2015

Title page of Nicolas Copernicus, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Basel, 1566), available at wikimedia commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:De_revolutionibus_orbium_coelestium.jpg) (23 July 2015).